As preparation for our docuseries, “Women in the Labor Movement” on May 31 at the Gail Borden Library, we decided to do some articles on the history of women in the labor force. The March newsletter told the stories of young girls working in the textile Mills in Lowell, Massachusetts and in two rayon companies in Elizabethtown, Tennessee, in the early and late 1800s. In both cases, those young girls organized and tried to get better wages and working conditions. In the footnote of that article, I shared information about my father who worked at the Whitnel Mills in Whitnel, N.C. My father worked in textile mills as a teenager and later as a foreman when he was a young man in the late 1940s and early 1950s. This article focuses on the Whitnel Mill, which employed whole families, including young children during almost half of the 20th century, and it traces what happened to one of the children and her descendants.

In the early 1900s, child labor was still prevalent; however, some Americans looked around and realized that children were being mistreated. They demanded an end to “child slavery” and wanted children to have educational opportunities and a chance for a better life. In 1904, some progressives set up the National Child Labor Committee. In three years, they had a charter from Congress and hired investigators to travel around the country and document the lives of children working in all types of industry, hoping to convince Congress to do something.

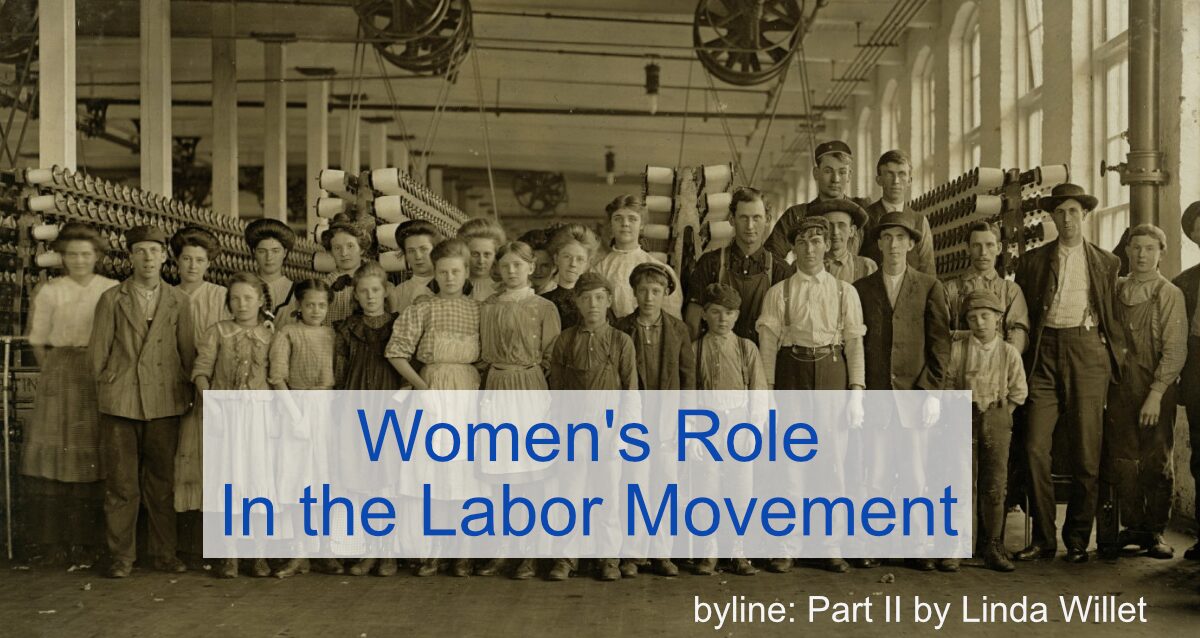

One of the people who answered this call was Lewis Hine, a young man born in Wisconsin who had quit school during his teenage years to support the family when his father died. Lewis continued his education later and moved to New York where he became a schoolteacher. In 1908, Lewis quit his job and became an investigative photographer for the National Child Labor Committee, travelling throughout the U.S. photographing and documenting the lives of children working in textile mills, coal mines, meatpacking houses, canneries, agricultural settings, and on the streets selling newspapers and shining shoes, etc. Hine’s work was dangerous because industry owners did not want America to see the poor working conditions and demands made on young children. Many of these industries hired people with large families because they knew they could pay children less than adults.

To get into these work environments, Hine took on different identities. He pretended to be a Bible salesman, fire inspector, industrial photographer, postcard vendor, etc., and made up reasonable excuses for talking to the children and finding out facts and figures. Hine added captions to his photographs. When he was not allowed inside, he took photos when the children were entering or leaving the workplace.

In December 1908, Hine took one of his most famous photographs at the Whitnel Mill where my father worked years later. Hine said that out of 50 employees, there were 10 children working at the mill. The young girl he photographed was 51 inches high and had been working at the mill for a year. She did not know her age and said, “I’m not old enough to work, but I do just the same.” The children at the Whitnel Mill made 48 cents a day and worked 12 to 16 hours a day, which included nighttime work and exposure to dangerous machines. (Sidenote from Linda. My dad used to tell us that the spinner’s job was one of the most difficult factory jobs because there are four sides to the machine, and you have to work all four sides.)

Unfortunately, the photograph taken in 1908 did not have the name of the child, but in 2007, Joe Manning, a journalist, attempted to identify her by contacting a local newspaper near Whitnel, the Lenoir News-Topic. When the paper ran the photo, a man in the community believed that the child in the photo was his grandmother, Cora Lee Griffin. An expert in photo identification agreed that the girl in the picture is Cora Lee, and the 1910 census seems to confirm that identification because Cora is listed as a spinner in the Whitnel Mill in that census, and her father and sisters also worked in the mill at that time.

Manning interviewed Esther Hoyle, Cora’s daughter, on February 1, 2007 (almost 100 years later). Esther said that she thought her mother stopped working at the mill when she got married; however, the 1920 census showed Cora and her husband working at the mill when they had two children and were living near Cora’s parents. Ten years later, Cora was a stay-at-home mom. When Cora talked to her children about the mill, she said that her boss liked her and thought she did a good job, but she wasn’t tall enough to reach the spinning machine and had to stand on a box to do her work.

When asked whether she thought her “mother was in a bad situation” as a child, Esther responded “Yes” and said that her mother left school in the sixth grade to work full time and regretted not finishing school. Cora told her children that she worked to help with family expenses, and her parents probably did not realize the value of an education at that time. Cora grew up on a family farm.

Esther said that Cora insisted that all of her children graduate from high school and attend college as many years as they wanted. All of Cora’s five children followed her wishes. Esther went on to get a master’s degree and taught high school and community college English courses. An older sister was also a teacher. Another sister and brother went to business schools. The youngest brother earned a PhD from Duke and was a professor and an archaeologist.

When asked if her mother thought she had a good childhood, Esther said that her mother believed she had made the most of what she had at that time, but her biggest regret was her lack of education. Esther shared that Cora loved music and played the pump organ and sang a lot. She was the church organist for many years and taught Sunday school for 55 years. Cora died on June 3, 1985, a month short of her 89th birthday. She was unaware that her photo and those of other children photographed by Hine helped to change child labor laws in the United States and gave children a chance to complete their education.

From 1908 to 1924, Hine continued to photograph children in the workplace, and the NCLC organized exhibitions and displayed the photographs to educate the public about the exploitation of children. In 1916, the photographs and testimony convinced Congress to pass the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act of 1916, which required that children be age 14 to work in manufacturing and 16 to work in mines. Night work was prohibited for anyone under 16. This act was later declared unconstitutional, but changes had been made in many states by that time, and by 1920, there were half as many children in the labor force. However, it was thirty years after Hine took Cora’s photograph when the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 finally ended “oppressive child labor” in the U.S. This act is still the primary child labor law today, and we need to be vigilant since the Florida House recently passed a bill that allows minors ages 16 and 17 to work more hours per week and on Sundays and holidays, and the Florida legislators are trying to loosen work restrictions regarding 14-year-old children.

Hine’s photographs can be seen throughout the U.S. in museums and online. They can be found at the Library of Congress, National Archives, Art Institute of Chicago, and the N.Y. Museum of Modern Art.

References

Go to Archives.gov and search for “Teaching with Documents: Photographs of Lewis Hine: Documentation of Child Labor

https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu

https://lsintspl3.wgbh.org

https://www.loc.gov

Search for Lewis Hine

Wikipedia.org

Search for Lewis Hine