What if you had five hungry school-age children and had to divide one fast-food hamburger among them and also find enough milk and baby food for two younger children to eat? That’s the situation Ruby Duncan found herself in during the 1960s.

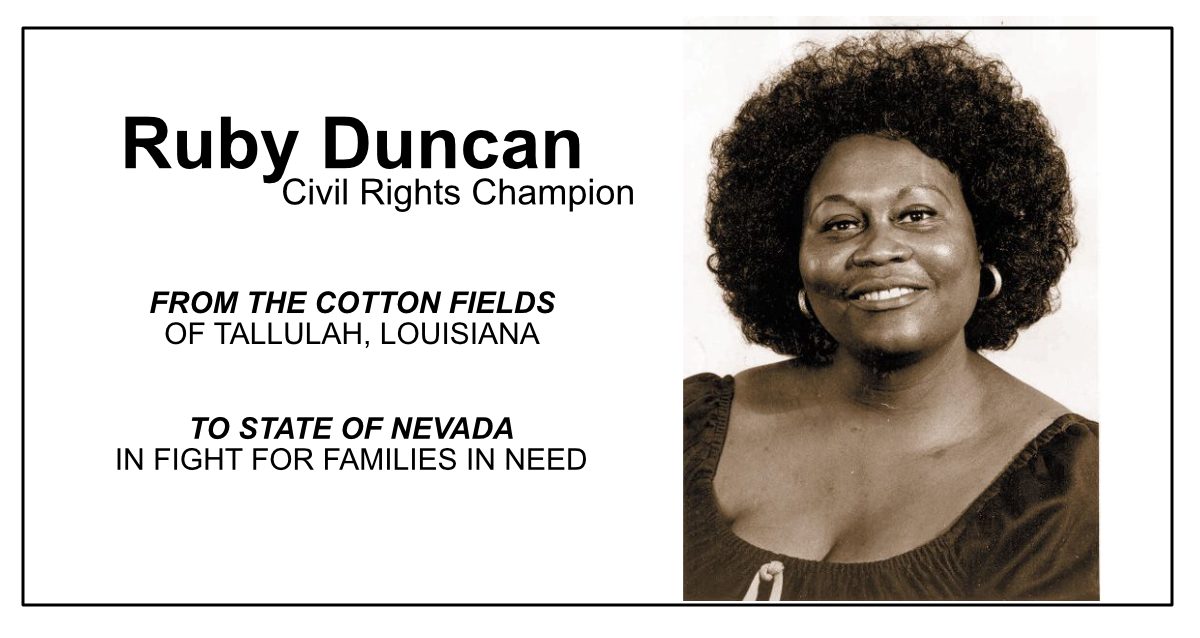

Ruby was born into a sharecropper’s family in Tallulah, Louisiana, in 1932. Both parents had died by the time she was four, and relatives took her in. For six months of the year, she picked cotton. The other six, she attended a Black school 8 miles from her home. When she was in ninth grade, she left school to work 80 hours a week as a waitress.

At the age of 21, Ruby moved with her family to Las Vegas in search of a better job and a better life. For several years, she worked as a hotel maid but was fired for organizing other maids and demanding higher pay. Ruby did not give up. Eventually, she got a job as a short-order cook at the Sahara Resort and Casino on the Vegas strip. After slipping on fried grease and oil on the floor when carrying large platters of food, she fractured her back, both knees, hip, and shoulder and spent a year in and out of the hospital in 1966 having numerous surgeries. She was divorcing her husband at the time and requested a retraining program from the State Welfare Department because she couldn’t pick up heavy boxes, but she was told nothing was available.

Unfortunately, Ruby had to go on welfare, which was $190 a month for her family of 8 (less than half of what families in NY, NJ, and Alaska received). Also, Black mothers in Nevada received less money than white mothers. Ruby said that many of her family’s meals consisted of corn bread and onions, which she fried in Vaseline since she couldn’t afford cooking oil. The federal government had set up the food stamp program in 1962, but Nevada refused to accept the federal money to help its residents living in poverty.

A year later, in 1967, Congress passed legislation requiring welfare recipients to attend training programs. The only job training program available in Ruby’s area was a sewing class that paid $25 a week for attending 40 hours of instruction. However, the class provided more than sewing instruction to Ruby and the other mothers. Here, they bonded together and talked about their poverty and frustration with the welfare system in Las Vegas, which included welfare workers coming into their homes at night and searching their rooms for any cash that someone might have given them. There was also a rule that any man in the house must leave for the woman to collect welfare. The women were furious about the degrading treatment they received and decided to form the Clark County Welfare Rights Organization with Ruby as their leader to fight for better rights. Right away, they started talking to representatives in the Nevada legislature, but no one seemed to care, and the women decided they needed to protest.

Ruby’s participation with the other mothers led her to create the Nevada Welfare Rights Organization. These women caught the attention of Dr. George Wiley, a chemistry professor and leader in the civil rights movement, who was one of the founders of the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO). Like the women in Nevada, Wiley wanted to reform the welfare system in his state of NY because it was harsh and degrading to poor people. Even though President Lyndon Johnson had set up national programs known as the War on Poverty, there were not many changes in Nevada. Dr. Wiley trained Ruby and the other women in Nevada and enlisted young lawyers and women’s rights activists who helped the women file legal papers and gave them advice.

The leaders included Ruby Duncan, Mary Wesley, Alversa Beals, Emma Stampley, and Essie Henderson. The situation became worse in 1968 when Richard Nixon was elected. He made jokes about welfare that portrayed poor mothers as “welfare queens” who collected checks and continued to have children, so they didn’t have to work. George Miller, the head of the Nevada Welfare Department, agreed with the Nixon policies. Duncan fought back by organizing protests, marches, and political events. Wiley and Duncan were incensed in 1971 when Nevada cut 75% of the welfare check given each month to women with children and entirely dropped most of the women in Nevada from the welfare rolls, falsely accusing them of fraud. Ruby was one of the women who was dropped.

This event motivated Ruby to take stronger measures. She organized two marches of welfare mothers and children to protest this action and decided to make her point by getting the attention of the casino owners (mob bosses) who controlled the money in Las Vegas. In the first march on March 6, 1971, over 6000 people marched down the Las Vegas strip, singing “We Shall Overcome,” and shut down business for several hours for most of the casinos, including Caesars Palace. This march attracted reporters and national attention and forced Americans to recognize the hunger of children living in poverty. To protect the women from the police and public, Ruby invited celebrities and activists like Jane Fonda and Ralph Abernathy to march with them and show support. In spite of murder threats, the women marched to the Sands Hotel on the Strip one week later and sat down in the middle of the street when the Sands locked them out. The casinos took the losses and within two weeks, a federal judge ordered that all the mothers cut from the welfare program must be reinstated right away.

With the help of the NWRO, the women continued to organize sit-ins and eat-ins. To protest Nevada’s refusal to accept food stamps to help needy families, Duncan and her friends brought busloads of children to the Palms Restaurant at the Stardust Hotel on Feb. 8, 1972. The children were told to order the most expensive food on the menu, and when Duncan refused to pay the $600 bill and told the waiters to bill the state of Nevada, she and Wesley were arrested while the other women took the children home. Duncan told the newspapers that the group was trying to let America know that welfare families did not have enough to eat, and the children rarely had a piece of fruit.

A year later, 1973, the group’s hard work led to Nevada participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (Federal Food Stamps) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). It was the last state to accept the program.

Duncan served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Miami in 1972 and returned home, thinking about how her community could create programs to help themselves. She became a co-founder of Operation Life, a nonprofit that provided community services in West Las Vegas. The women convinced a bank to donate an empty hotel to their cause and then applied for federal grant money to create a clinic, child care center, lunch program, employment training program, and a library, which were run by women in poverty to help women in poverty. In the 1980s, they built houses for low-income families.

George Miller was still at the helm of the Nevada Welfare Department and very angry about Ruby’s success in helping people. On the day before Thanksgiving, 1976, Miller padlocked the Operation Life building and accused the organization of fraud. This led to a six-week audit, which showed that only four cents were missing, and a court trial where the NWRO lawyer represented Operation Life. The judge decided to visit the facility and declared that the accusation of fraud was baseless.

Ruby has received numerous awards and national recognition for her efforts and achievements. In 1971, McCall Magazine chose her first among women “making significant contributions to the nation,” and In 1980, she was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to the White House Conference on American Families,” where she emphasized the importance of good childcare so single mothers could go to work and achieve economic independence. In 2008, she was awarded the Margaret Chase Smith American Democracy Award for political courage. Her courage is an example to all of us. In spite of the threats on her life, Ruby said, “I wasn’t afraid of nothing…. I had children. And they got to be fed.” and “If you want your life to get better, you got to fight for it.”

Ruby continued as head of Operation Life until her retirement in 1990. In 1992, the facility closed. She is still talking to young people and encouraging them to be politically active to improve their lives. Most of all, she says that everyone needs to vote, and they should mobilize and work together if they are unhappy.

Sources

Orleck, Annelise. Storming Caesars Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty, 2005. This book was also made into a PBS documentary.

www.guides.library.unlv.edu “An Exploration of Black Las Vegas Through the Resources in UNLV Special Collections and Archives” (An interview with Ruby Duncan by Claytee White on March 2, 2013)

www.kntv.com news clip

Google “Ruby Duncan: A Longtime Champion for the Rights of Nevada Families in Need.”

www.reviewjournal.com

Bracelin, Jason. Las Vegas Review Journal, March 18, 2023.

”You Poor, You Stupid” discusses the PBS documentary “Storming Caesars Palace”

www.reviewjournal.com

Wanser, Brooke. Las Vegas Review Journal, 2017.

”Pioneering Las Vegas Activist Ruby Duncan, 5 Others to Be Honored” discusses the achievements of Ruby Duncan and the Clark County Welfare Rights Organization

wikipedia.org

Google.com “Ruby Duncan and civil rights”